A render farm in Haskell

March 07, 2010 at 07:40 PM | categories: Uncategorized | View CommentsBrowse the full source of the ray tracer on GitHub

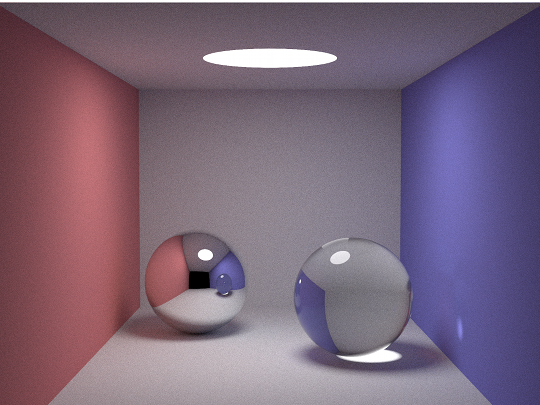

A few weeks back I came across the smallpt ray tracer by Kevin Beason. smallpt is a global illumination renderer written in 99 lines of C++. Since it uses a Monte Carlo technique to randomly cast rays and average the results, the longer you can leave it running, the better the image will look. Kevin's code uses OpenMP to split calculations across more than one CPU core.

Since ray tracing is the sort of mathsy task that Haskell excels at, I wanted to see how what a Haskell port of Kevin's code looked like. That code itself isn't the subject of this article, because what I wanted to write about instead are the techniques you can use to distribute Haskell code across multiple cores. These techniques range from parMap (which is almost transparent to the program, but provides little control over where the code runs) to brute-force distribution of work across several machines.

parMap

One of the things I love about Haskell is that its pure functional nature makes it straightforward to parallelise code within a single machine. You can normally take any code implemented in terms of map and parallelise it with parMap, from the Control.Parallel.Strategies module. parMap will use lightweight threads provided by the runtime to apply a function to each element in a list in parallel.

The parMap function accepts an argument that controls the evaluation strategy. Most of the examples I've seen use parMap rwhnf ("weak head normal form"), which only evaluates the outside of a data structure; the insides of your data are evaluated lazily, and this doesn't necessarily happen on one of the parallel lightweight threads as intended.

To evaluate anything more complicated than a list of simple values in you'll probably need to use parMap rdeepseq, which recurses inside your data on the lightweight thread so that it's fully evaluated by the time parMap finishes. rdeepseq is defined in terms of the Control.DeepSeq module, and if you've defined your own types, you'll find you need to implement NFData.

A final note on parMap: don't forget to compile with the -threaded flag, then run your program with +RTS -Nx, where x is the number of CPU cores you want to distribute across.

forkIO

Haskell supports good old-fashioned manual concurrency with functions in the Control.Concurrent module. This works broadly the same as in other languages:

- Use

forkIOto start an IO computation in parallel with the current thread - Threads can communicate through objects called MVars: create a new one using

newEmptyMVarornewMVar - MVars can be empty, or they can hold at most one value:

- Read a value from an MVar using

takeMVar. This will block if the MVar is currently empty. - Write a value to an MVar using

putMVar. This will block if the MVar is currently full. CallingputMVarwakes up one of the threads that's blocked insidetakeMVar.

forkIO starts a computation in parallel and lets you essentially forget about it; mvars are an effective way of encapsulating mutable state shared between more than one thread. What I like about this is that there's no error-prone manual locking like you'd find in, say, Java or .NET. Although forkIO and mvars give you full control over thread scheduling, they're not drop-in replacements for sequential calculations in the same way as parMap.

Brute force

The previous two techniques rely on the multi-threading capabilities of the Haskell runtime. They know nothing of what's happening outside of a single Haskell process, which limits them to the number of cores present in the machine. To go beyond that, separate instances of your program will need to communicate with each other over a network.

In my Haskell port of smallpt, I used this technique to run as many instances of the program as needed: one process per core on the local machine, and one process on each of a range of instances running on Amazon EC2. The communication protocol is as simple as possible: plain text over pipes. I used ssh to communicate with the EC2 instances, so from the outside there's no difference between a local instance and one running on the cloud.

The algorithm goes as follows:

- Establish the work you need to do. In this case, a work item is one line in the final rendered image.

- Split the work into tasks you can give to the worker processes. For simplicity, I'm splitting the work equally to give one task to each worker.

- Launch the workers and provide them with the task inputs. Since workers accept plain text, I take a

Workobject andhPrintit to a pipe. - When each worker finishes, collect its output. Outputs will come back in an unpredictable order.

- When all the workers are done, sort all of the outputs into the same order as the inputs

The coordinator is the program you launch from the command line, and it deals with things like command-line parsing, executing the distribution algorithm above, and writing a .png format image at the end. The worker processes are themselves instances of the smallpt executable, launched with the -r flag. In effect what each smallpt -r does is:

-- Render one line of the scene and return it as a list of pixels

line :: (Floating a, Ord a, Random a) => Context a -> Int -> [Vec a]

runWorker = interact (show . map line . read)

One potential flaw in this is that, because you're communicating over plain text, the Haskell type system won't trap any errors: there isn't necessarily any link between the types in the coordinator and the types in the worker. The interface to the distribution code consists of a Coordinator a b record, where a is the type for inputs to the workers, and b is the type that the workers produce as output:

data (Show a, Read b) => Coordinator a b =

Coordinator { submitWork :: [String] -> [a] -> IO [b],

runWorker :: IO () }

coordinator :: (Read a, Show a, Read b, Show b) => (a -> b) -> Coordinator a b

coordinator worker =

Coordinator { submitWork = submitWork',

runWorker = interact (show . map worker . read) }

Most of the multi-threading code lives inside the submitWork' function which implements the algorithm above:

- Given a list of worker commands lines (

[String]) and the work itself ([a]), produce a list of tuples of workers and tasks - Using

forkIO, fork one thread per worker. Inside each of these threads: - Start the worker process itself (via

createProcess shell) - Write an

[a]to its standard input - Read a

[b]from its standard output - Put the

[b]into an mvar shared between all worker threads - Back in the coordinator thread, call

takeMVaronce for each worker. This produces a list of results as a[[b]]. - Once all the workers have finished, collapse the results into a

[b], making sure the output list comes back in the same order as the original inputs. If any of the workers encountered an error, useioErrorto fail the whole operation.

This approach works remarkably well for this simple ray tracer demo. But it has some serious flaws that you'd want to avoid in a production system:

- Any failed worker process invalidates the whole set of results. Even in the absence of software bugs, machines can fail any time (consider how often disks fail when you've got 4,000 of them). The coordinator should recognise transient errors and retry those tasks; it might choose to take workers out of rotation if they fail repeatedly.

- All machines are assumed to be equally powerful. This is rarely the case: for instance, workers running on my Mac here finish far sooner than ones on my small Amazon instances.

- All work is assumed to take the same length of time to complete. Even in this simple ray tracer, plain diffuse surfaces are much easier to calculate than reflective (shiny) ones or refractive (transparent) ones.

- Tasks are allocated up front. If a worker finishes early -- maybe because it's running on a Mac Pro, or because it generated a line of empty space -- it can't have any more work allocated to it.

- Workers can't spawn other workers. In my code the worker function isn't declared in the IO monad, so it can't interact with anything. Even if it could, it would need to know about all of the other workers so that it could pick an idle core to do work on.

Next time I'll talk about some of the code in the ray tracer itself, as well as some approaches you'd use in practice to correct these flaws in the demo.